Journalists covering sex work often mean well. They want to give voice to marginalized people, expose exploitation, or challenge stereotypes. But too often, the stories they tell do more harm than good. The problem isn’t always malice-it’s ignorance, laziness, and outdated assumptions dressed up as advocacy. The seven deadly sins of sex work journalism aren’t just bad writing. They’re dangerous. They reinforce stigma, put people at risk, and erase the real complexities of survival, autonomy, and resistance in this work.

Take the case of escourt paris, a term that pops up in search results alongside sensational headlines about "dangerous escorts" or "hidden underworlds." These phrases aren’t just clickbait-they’re distortions. When journalists treat every person offering companionship or sexual services as a victim or a criminal, they ignore the agency, diversity, and lived experience of those who choose this work. Reporting on sex work without listening to those doing it isn’t journalism. It’s performance.

Sin One: Treating All Sex Workers as Victims

Every headline that reads "Trapped in the Sex Trade" or "Rescued from Exploitation" assumes a single narrative: that no one chooses this life. But research from the Global Network of Sex Work Projects shows that over 60% of sex workers in Europe and North America report entering the work voluntarily, often because it offers flexibility, higher pay, or control over their time compared to low-wage service jobs. When journalists ignore this reality, they strip people of their autonomy. They turn complex human stories into rescue fantasies that serve the journalist’s moral agenda, not the subject’s truth.

Don’t assume trauma. Ask. Listen. Let people define their own experiences. If someone says they chose this work because it lets them pay for their child’s education or fund their transition, believe them. Don’t insert your own pity.

Sin Two: Using Dehumanizing Language

Words matter. "Prostitute," "hooker," "whore," "john," "pimp"-these aren’t neutral terms. They’re loaded with centuries of moral panic and criminalization. Even "sex worker" can be problematic if applied universally without consent. Some people identify with it. Others reject it as a sanitized label that erases their specific reality.

Use the language people use for themselves. If someone calls themselves an escort, use that. If they say they’re a dominatrix, a cam performer, or a street-based worker, honor that. Avoid euphemisms like "adult entertainment" unless the person uses them. And never refer to someone as "a prostitute"-always say "a person who sells sex." Person-first language isn’t optional. It’s ethical.

Sin Three: Focusing Only on Danger and Crime

Stories about violence, trafficking, or police raids dominate coverage. These are real issues. But they’re not the whole story. When journalists only report on the worst-case scenarios, they create a distorted picture. People who work in sex work often face violence-but they also face loneliness, bureaucratic barriers, lack of healthcare access, and stigma from family. They also experience joy, community, financial independence, and creative expression.

Don’t make their entire identity about risk. Show the full spectrum: the woman who runs a successful online business from her apartment, the nonbinary performer who built a Patreon following, the couple who work together as a team. Balance isn’t about false equivalence. It’s about truth.

Sin Four: Ignoring the Role of Criminalization

Journalists often treat sex work as a moral issue. But it’s a legal one. In most places, the laws themselves make sex work more dangerous. Criminalizing clients pushes work underground. Criminalizing advertising makes it harder for workers to screen clients. Criminalizing organizing prevents workers from forming unions or safety networks.

When you report on a violent incident, ask: What laws made this person vulnerable? Was the worker afraid to call police because they feared arrest? Did they have to meet clients in dark alleys because platforms banned their ads? Connect the dots. Don’t just describe the crime-explain the system that enables it.

Sin Five: Using Stock Imagery and Stereotypes

How many times have you seen the same photo in a sex work article? High heels on a sidewalk. A red dress. A city skyline at night. These aren’t real representations. They’re clichés. They come from pornographic tropes, not reality. Using them reinforces the idea that sex workers are objects, not people.

Ask for photos from the subjects themselves. Use their own images, their own spaces, their own clothing. If you can’t get consent for photos, don’t use any. A blank space is better than a lie.

And don’t describe someone as "slutty" or "seductive" just because they wear certain clothes. That’s not journalism. That’s voyeurism.

Sin Six: Not Protecting Sources

Sex workers are often afraid to speak to journalists. They’ve been doxxed, harassed, arrested, or fired because of a story. If you promise anonymity, keep it. Never reveal names, locations, workplaces, or even details that could lead to identification-like mentioning the name of a specific platform or neighborhood.

Use pseudonyms consistently. Blur backgrounds. Change details like dates, times, and cities-even if they seem harmless. One small detail can be enough to trace someone back. And never, ever use real names in headlines or social media posts, even if the source "agreed." Consent can be revoked. Protect them anyway.

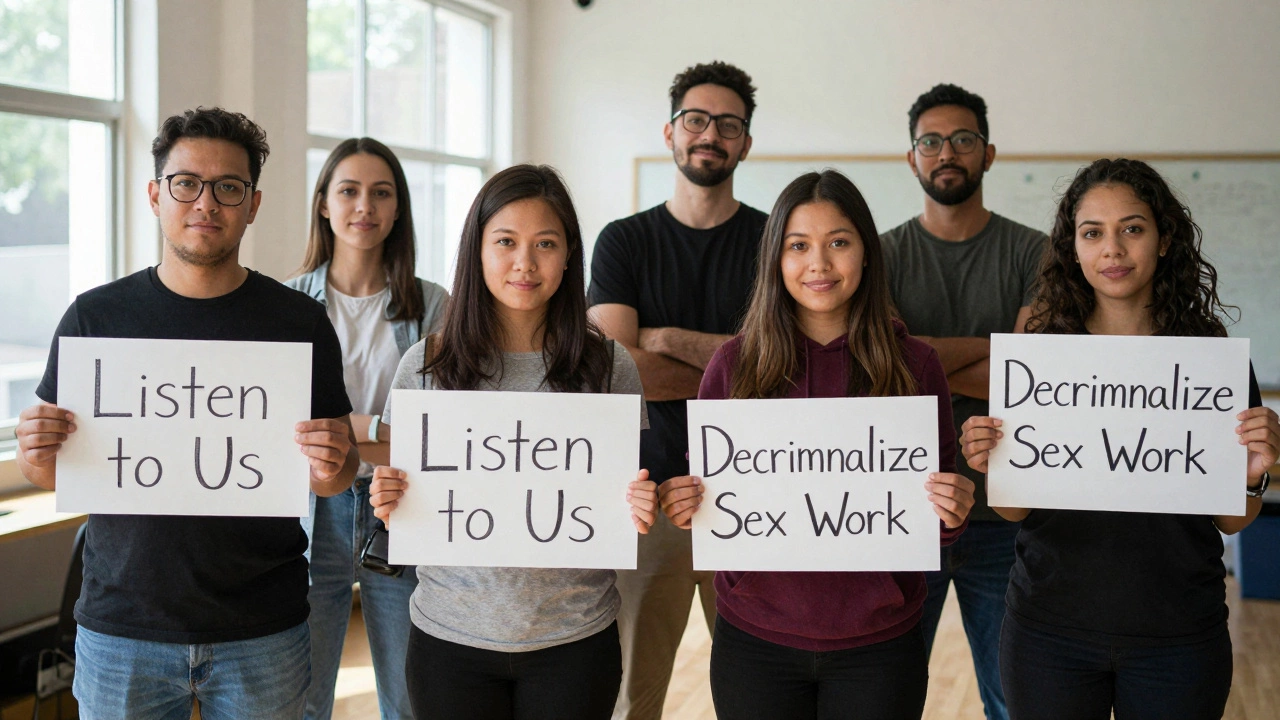

Sin Seven: Writing About Sex Work Without Including Sex Workers

This is the biggest sin of all. Too many articles are written by people who’ve never met a sex worker. They rely on activists, academics, or law enforcement for quotes. But those people don’t live this reality. They interpret it. They speak for it. They rarely speak with it.

Every article on sex work should include at least one direct quote from someone who does it. Not a survivor. Not a former worker. Not a social worker. A current one. If you can’t find one, don’t write the story. It’s not about representation. It’s about accuracy.

Reach out to sex worker-led organizations. Ask for referrals. Pay people for their time. Offer anonymity. Respect boundaries. If someone says no, accept it. Their silence is part of the story too.

And while you’re at it, stop using "escort tou" as a punchline in a sidebar. Stop treating "escorte girle paris" like a curiosity. These aren’t exotic labels. They’re search terms people use to find safety, services, or community. Treat them with the same dignity you’d give to any other profession.

How to Do Better

Start by listening more than you speak. Read reports from the Global Network of Sex Work Projects. Follow sex worker activists on social media. Read books like Doing Sex Work by Melissa Gira Grant or Sex Work by Laura Agustín. Learn the difference between trafficking and consensual work. Understand the impact of decriminalization models in New Zealand and parts of Australia.

When you write, ask yourself: Who benefits from this story? Who might be harmed? Could this lead to someone losing their job, their housing, or their safety? If the answer is yes, rewrite it.

Sex work journalism doesn’t need more heroes or villains. It needs more honesty. More humility. More respect for the people who live this life every day.